|

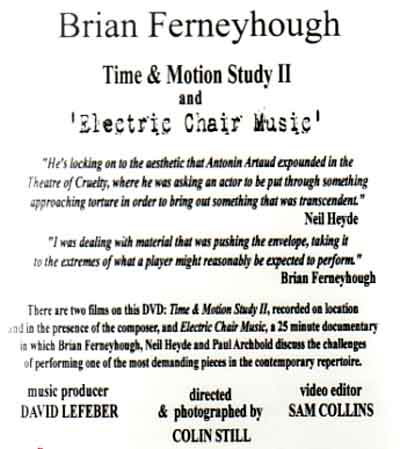

Brian Ferneyhough

Time and Motion Study II & Electric Chair Music

Two films by Colin Still

Neil Heyde: cello

Paul Archbold: electronics

a DVD performance and documentary, the first film to show the composer at work with performers

£12.50 from Academy Chimes

Brian Ferneyhough’s manuscripts are amazing to behold. They can stretch a metre across, with so many lines above and below the stave that it doesn’t take many bars to fill a page. Technically his music is fiendishly complex, but the real challenge is how a performer experiences the process intuitively.

This DVD is essential viewing because it shows a performance of Time and Motion Study II in progress. It is wonderful because shots of the manuscript are shown while the music plays*: sight reading scores like this is not an option for most people, so it’s much easier to appreciate selected moments like these in detail. With DVD technology, it’s possible also to freeze the film long enough to work out what’s on the page, and relate to its translation in sound.

More importantly, though, Colin Still's film makes it possible to get closer to the performer than one would ever dare in real life. This matters in Ferneyhough, because this is music to be appreciated viscerally as well as in the abstract. Here we see the muscles on Neil Heyde’s face tense, so we can relate to his feelings.

Despite the technical wizardy, Ferneyhough’s music operates on a basic, fundamentally human and intuitive level. That’s why involuntary grunts and grimaces are part of the overall experience : the performer is revealed on a basic, primitive level. He’s operating in his subconscious, far beyond the constraints of convention.

Ferneyhough’s original working title for this piece was “Electric Chair Music”. He abandoned it as too specific and limiting. But, it does help put things into perspective because this music pits man and cello against machines. Heyde is surrounded by a rat’s nest of wire and sound devices. Even his cello is infiltrated, microphones hidden under the fingerboard. The electronics operate like a living force, observing the performer intimately, then distorting everything he does. Moreover, he has to listen, in order to respond and react. Since he’s hearing himself played back at several different time intervals concurrently, further blurring reality and unreality, realtime and recorded time.

The film also shows Ferneyhough’s expressive markings. As Heyde says, anyone can read “black splodges” on a score, but Ferneyhough’s “emotive signposts” challenge a performer to engage far more deeply. For example, there’s a passage with rapid staccato fingerings and bowings alternating. “Reptiles and insects….a praying mantis”, writes the composer. .

In the film, Ferneyhough explains that notation evolves. It is a suggestion, made to spark a performer’s creativity, so that he can give something personal and unique to the music. Sometimes, the instructions are (deliberately) almost impossible to achieve. As Heyde explains, there’s a marking “machine gun fire”. No one can play that rapidly or harshly, he says, but that’s fine, because this music is about possibilities. Imagination isn’t bound by physical limits.

Because Ferneyhough himself was involved in this performance, it’s an opportunity to see how he reacts. At one point, after a dense, harrowing passage, black with images of the sound system and Heyde’s anguished face, there’s sudden silence. Ferneyhough is shown, in his white suit against a white wall. This is sensitive camera work at its best, picking up intuitively on what’s happening in the music and expanding the impact.

Heyde says he can’t understand the Grand Adagio, because the slow grinding sounds seem to lead nowhere. Ferneyhough says it’s “immersion in total negation” before the breakthrough of “sublimity” that follows. He refers to the ideas of Antonin Artaud, where struggle is a prerequisite for freeing the spirit. Facing extreme challenge stretches limitations until they burst and are obliterated. That allows a new kind of consciousness to emerge, transcending all that has gone before.

At the end of the piece, Heyde and his playing seem caught up in a cataclysmic psychic battle. Then, abruptly he jerks and, for 8 seconds, he remains immobile, before a final jerk of release. Perhaps he’s reached that strange stillness?

I learned this music from an audio recording and will probably listen to that more frequently than watching a DVD. But this film has expanded my understanding of the piece, and of the composer, so much that it will exist in memory, in parallel, whenever I listen again to Time and Motion II.

This is an extremely valuable film, and should be seen and heard not just by people interested in new music, but by all those interested in creativity and the human condition.

Anne Ozorio

* The potential of performance plus score has been surprisingly little exploited since DGG's pioneering pluscore of Beethoven/Pollini, and see also Eulenberg Audioplus

Read Martin Iddon's research article - On the entropy circuit: [Contemporary Music Review, Volume 25 February–April 2006: This article discusses aspects of the relationship between the vocalising cellist and the live electronics in Brian Ferneyhough's Time and Motion Study II . [Editor]

|