Tchaikovsky Eugene Onegin

BBC 4 film, transmitted 4 July 2004

WNO Orchestra and Chorus/Tugan Sokhiev

Director: James Macdonald

Designer: Tobias Hoheise

Lighting: Andreas Grüter

Choreographer: Stuart Hopps

Television Producer: Hefin Owen

Tatyana: Amanda Roocroft and Onegin: Vladimir Moroz (pictured)

Lensky: Marius Brenciu

Olga: Ekaterina Semenchuk

Mme. Larina: Suzanne Murphy

Filipyevna: Linda Ormiston

M. Triquet: Robert Tear

Prince Gremin : Brindley Sherratt

WNO's Eugene Onegin was filmed at the New Theatre, Cardiff, so successfully that a DVD version must be envisaged and is eagerly awaited. A favourite opera of mine, of which it is impossible to tire, this relatively modest production is one of the most satisfying I have heard and seen, and it is ideal for the small screen.

The seven lyrical scenes are given straight through (in the theatre, it took four hours!). The director and his team bring all the characters vividly to life and their acting in close up is very watchable - not always so with filmed opera.

Tobias Hoheise's simple, uncluttered sets (designed for touring) were beautifully lit by Andreas Grüter and make perfect backgrounds for the action and for the internalised musings of the protagonists in the pauses when they articulate their private thoughts. There is a continuing critical tension between the assumed public demand for lavish, costly sets (often on stages far too large for the scenes) and the revolution in affordable sets as demonstrated in college productions which, with imaginative design and lighting, can offer equal satisfaction. A good example was the vilification of the Gubay operas at the Savoy because the audiences were supposedly short-changed with the sets; Musical Pointers took a contrary view.

The WNO production of Eugene Onegin never pretends to be wholly realistic and we are always conscious that we are watching an opera, but an opera with one of the best of all libretti, which tugs at your heart again and again. The tragedy is more powerful because of the sense of its outcome not being inevitable. The emotions are telling and indeed harrowing as brought into the intimacy of one's home.

Amanda Roocroft characterises the young Tatyana perfectly and she is later ideal as the mature Princess who pays back Onegin for her youthful humiliation. I was glad to see Cardiff and Brussels prizewinner Marius Brenciu, about whom I had doubts previously, as a thoroughly convincing Lensky, who made us wish the duel could be avoided as strongly as those on stage urged! His tenor was subtle and beautiful, far more mellifluous than at a concert in London a couple of year ago. All the parts in this production are studied and represented to perfection, the chorus members each acting and dancing as credible individuals, and the musical flow, under the baton of the absurdly young Tugan Sokhiev is as fine as any I can remember.

° I append below extracts from a thoughtful review in OnLineReview which readers may not have seen. I was untroubled by the top hat which disturbed Simon Heilbron at Sadlers Wells!

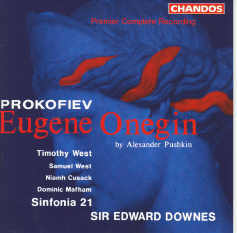

° The telescoping of Pushkin is a genuine problem; things move fast, especially as televised without any intervals! (In the theatre it took four hours, so I read on Seen&Heard.) To fill in some of what is missing, and enjoy Pushkin's astonishing verse drama in English translation, I recommend as indispensible the Chandos recording by Edward Downes of Prokofiev's Eugene Onegin Melodrama in sixteen scenes (Chandos CHAN 9318/9).

OnLineReview- - It is hard for us (as it must have been for the composer himself) not to regard Tchaikovsky's life as a particularly lurid opera plot derived from a Russian novel. The story of Eugene Onegin takes a somewhat different turn, but the themes of sexual self-denial and unrequited passion, of wasted opportunity and consuming guilt, are tellingly similar.

Pushkin's hero is a man in denial whose emotional dishonesty has tragic consequences. Sophisticated Onegin spurns innocent country girl Tatyana; flirts with his best friend Lensky's fiancee and then kills him in a duel. He returns after two years abroad to find Tatyana married, and realising his mistake, tries unsuccessfully to woo her away. It is the pair's fate never to taste the love they crave: that happiness , as they admit in the final scene, had once been so attainable, so close.

The requirement to condense Pushkin's verse novel into what Tchaikovsky described as seven lyric scenes has meant a certain telescoping of the drama. In the novel Tatyana does not fall in love with Onegin instantly, there is a passage of time before the famous letter scene in which she writes to him declaring her love. Similarly, after seeing Tatyana again in St. Petersburg Onegin bombards her with letters which go unanswered. In despair, he finally goes to her house as in the final scene of the opera.

These unseen narrative entr'actes would have been familiar to Tchaikovsky's audience who all read Pushkin from a relatively early age, but they are less so to a modern operagoer. This Welsh National Opera production's director, James MacDonald, has the difficult task not only to make these unsympathetic characters come to life but also convincingly to fill in the narrative gaps. Crucially, Onegin's first appearance towards the end of the opening scene must plant the seed which grows in Tatyana's mind, culminating in the letter scene. Tchaikovsky gives him only a few stilted lines to sing to Tatyana yet the audience must truly believe that she has fallen for this aloof, but attractive, poseur.

Unfortunately Onegin's entrance in this production has an alienating effect. He is attired in black frock coat with a ludicrously tall top hat -more undertaker than urban dandy - and he is played stiffly by Vladimir Moroz, a young star from the Mariinsky Theatre company. It is hard to imagine that even the most naive and impressionable country girl would be impressed.

Thankfully Onegin's stage persona strengthens as the production continues. The hairstyle changes accordingly, starting neat but becoming longer after his absence abroad, and then completely unkempt as, at the last, he vainly tries to destroy Tatyana's marriage. Moroz's icy detachment suits the snow-covered landscape of the duel scene, but it was disappointing that he appeared unable to bring greater depth to this fascinating role. It has to be said, however, that Moroz's voice, in contrast to his dramatic presence, is gloriously complex and powerful; The WNO have certainly done audiences proud in being able to attract international artists of this calibre. - - The role of Tatyana is taken by another glittering name, Amanda Roocroft. The voice, with its controlled vibrato, is mature, but Roocroft looks the part. At the beginning we see her girlishly lying on the grass engrossed in a romantic novel. In the ensuing letter scene, the immaturity is reinforced as she writes her misguided missive lying on her bed. Having despatched the letter, in probably the most memorable moment of the production, she blissfully throws her clothes around the room and goes to sleep in the morning sunlight.

Roocroft clearly conveys the chilling effect of Onegin's subsequent rejection and her discomfort at his boorish antics at her name-day celebration, all achieved through body language and eye contact.

It was an imaginative directorial idea to have Onegin produce Tatyana's original letter at the end to prove to her that she had pledged to love him. But again the short musical time-scale does not allow for such dramatic niceties to have any real impact, and the clumsy way in which Moroz pulled the letter from his pocket gave the impression of hasty afterthought.

Lensky is brilliantly played by tenor Marius Brenciu, a former Cardiff Singer of the Year. In the short time available, he convincingly works up into jealous rage as Onegin seduces his betrothed, Olga - one could almost feel his pain more keenly than that of the principal lovers.

The remainder of the cast are all equally strong. The veteran Robert Tear comes on as the absurd Monsieur Triquet and delivers his sentimental ditty with masterly presence. Even the tiniest of roles, that of Lensky's Second in the duel scene, is beautifully sung by David Soar.

Musical Director Tugan Sokhiev - - conducts his compatriot's score with flair, passion and drive; the orchestra respond in kind - - the music of Eugene Onegin contains much exposed woodwind and French horn writing, all superbly encompassed by the WNO players.

The minimal set by Tobias Hoheisel - this is a touring production, one should remember , is nevertheless highly effective. A partition across mid-stage, slightly offset and with a large cut-out, gives a sense of perspective and provides additional means of entrance and exit. Each of the seven scenes is subtly different, reflecting Tatyana's journey from the pastoral simplicity of the Larin estate to the urban sophistication of St. Petersburg . Hedges, windows, snow and mirrors were all simply but tastefully incorporated along the way. All leads inexorably to emptiness of the final scene , containing no more than Tatyana's daybed, her books and a tantalising glimpse of another life through the window.

Choreographer Stuart Hopps has done a splendid job of turning the chorus into dancers for the evening. Granted, they are not the Mariinsky Ballet, but in the fourth scene we were treated to a waltz, a cotillion and even a Ukrainian folk dance. In the penultimate scene, set in the pillared grandeur of St. Petersburg , the stage partition tended to obstruct an otherwise impressive polonaise.

Another reason the dance scenes were so successful is due in no small measure to Hoheisel's costumes - - of Tchaikovsky's time rather than the 1821 of Pushkin's. The intervening fifty years saw the rise in technology of aniline dyes and the consequent rise in bright colours - -

Simon Heilbron |