|

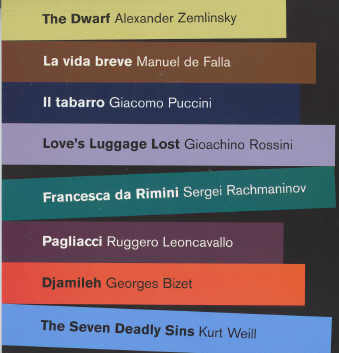

Opera North at Sadlers Wells June 22-26 2004

A mixed bag of one-acter double bills in London for a week, with tickets sold for each short opera separately. Single press tickets only, presumably in expectation of sell-outs (not fulfilled at our first visit), so critics were sat apart from their paying partners, not ideal for nights at the opera! A mixed bag of one-acter double bills in London for a week, with tickets sold for each short opera separately. Single press tickets only, presumably in expectation of sell-outs (not fulfilled at our first visit), so critics were sat apart from their paying partners, not ideal for nights at the opera!

Christopher Alden's Pagliacci troupe is a down at heel rock group; unconvincing to the point of acute embarrassment. Miming a full orchestra on electronic keyboard and drum kit was a joke that simply doesn't work. A disastrous start to the week's experiment, one to turn off equally the young that Opera North is seeking to woo to the cause, and older opera afficionados too.

Djamileh was quite other; a marvellous, precious Bizet score (available, without linking dialogue, on Orfeo C174881A) - unaccountably little known. A nasty little Arabian Nights story about Haroun's harem with month-long appointments, and heart-break for a slave who enjoyed  her temporary duties too well! her temporary duties too well!

The updating by Christopher Alden and translation to a sumptuous apartment in France brings it all close to we male voyeurs' knuckles, with Haroun a modern Arab assisted by his willing servant

Splendiano, who organises things and takes videos of the proceedings. The French libretto was given with side-titles at Sadlers Wells. The near-happy ending is subverted, very plausibly, by Alden who has Haroun strangle his latest mistress when he has got too fond of her!

Patricia Bardon is great as the slave of the month who moves Hanoun (Paul Nilon) to care too much, and the orchestra is in the capable hands of David Parry.

Remaining performance details:

Wed 23 Il tabarro (surtitled) La vida breve (surtitled)

Thu 24 Francesca da Rimini; The Seven Deadly Sins

Fri 25 Pagliacci; The Seven Deadly Sins

Sat 26 Il tabarro; Love's Luggage Lost; The Dwarf; La vida breve

P.S. We found David Pountney's Il Tabarro excellent in all ways, as did most reviewers; there are many reviews to endorse that judgment, e.g.

David Pountney's staging imbues Puccini's torrid depiction of jealousy and revenge with a brooding power to match the score's impassioned depiction of disenfranchisement and loss played out in, on and around designer Johan Engel's huge, tilted container, expressively lit by Adam Silverman. - -

Martin André conducts a searing reading of Puccini's richly orchestrated score, which subtly interweaves seething passion and expressive local colour. The orchestra play as if possessed (TheStageOnLine).

Not so his Weill Seven Deadly Sins the following day, with over-the-top degredation reminding us how he used to treat his wife, dramatic soprano Marie Angel, on stage; the audience loved it! And Rebecca Caine, her words mostly indecipherable, was no match for Lotte Lenya!

Nor could we enthuse about Christopher Alden's La vida breve, admired fulsomely by many critics, but which to our tastes strayed just too far from Falla's and his librettist's conception to win our sympathy (insistent blacksmiths' anvils being struck in a wedding dress factory, etc.......). So, perhaps best to refer you to the range of reviews on TheOperaCritic, of which our own feelings are best summarised in:

- - Engels gives us a clothing sweat-shop , exceedingly well-made and convincing, it is an eye-opener of a set , but it is not the right place for this story, which needs a cottage first and then a church or church steps; and the misplacing of the action is the first step in setting the production at odds with Falla. The second misstep is provided by Alden, who choreographs a sequence of actions which, for the most part, scarcely relate , and sometimes seem at odds with , the story being told by the words and music - - (A C Grayling in OnLineReviewLondon)

and to copy below a particularly thoughtful review of it, which encapsulates both points of view, from Zarzuela, a website new to me, one devoted to matters Spanish:-

Falla La vida breve Christopher Webber on Opera North's radical new staging ...

In staging a piece as unfamiliar as La vida breve, what is the production team's prime responsibility? Should they play a straight bat, sticking as closely as possible to what the creators wrote? Would that be doomed heroism for an opera so far removed from modern theatrical pacing and taste? Should they instead recast the work so radically as to effectively replace it? How fair is this to an audience largely unfamiliar with the original?

Nowadays we are inured to the howls of protest which used to greet Director's Theatre; and though that battle has been fought and lost, we may still be perplexed by a paradox. As musical preparation has become progressively purist, striving to approach ever closer the composer's ideal text, so stagings have become increasingly divorced from the writer's verbal and visual instructions. The resultant dislocation of sound and image is stimulating, sophisticated, and a sure symptom of a musical-theatrical tradition in at least temporary decline. It's what happens when old rather than new stuff becomes the centre of attraction. The museum is closed to new exhibits; so all we can do is put fancy new clothes on the old faves, fiddling while Rome burns.

So it is that the Auteur-director has become the bogeyman of opera, the (wo)man we love to hate. Which brings us to Christopher Alden, certainly much more the auteur of Opera North's La vida breve than Carlos Fernández Shaw. The writer did not set his libretto in a corrugated iron sweat shop, where the downtrodden women workers sew bridal gowns under hard fluorescent light, overseen by men in brown coats (de Falla's offstage chorus of blacksmiths) who when they aren't brutalising the workers stand around drinking mugs of tea. Nor presumably did he envisage the offstage tenor whose words articulate so much of the pain of the piece should be embodied as a muscular transvestite, whose fate as Heroine's Best Girlfriend is to have the shit kicked out of him by the brown coats. This happens during de Falla's sinuous transition to the final scene, whilst the heroine herself - spurned gypsy girl Salud - commits a gory ritual suicide. Earlier we have seen her engage in coitus interruptus with her feckless Paco, who soon after is caught snogging his brother-in-law on a table as they snort cocaine during the surging Spanish Dance de Falla provided for the wedding festivities. No dancing here, no costumbrista local colour, no picture-postcard Granadine exotics.

So far, you might think, so bad. Not so! The Spanish-Wagnerian, sacrificial spirit of the original is beautifully captured in slow, dignified, ritual movement, its intensity hardly ruffled even by the wild dance or choral interludes. The characters and scenario are more or less recognisably Fernández Shaw's, although Salud's Grandmother (Susan Gorton) becomes the hapless supervisor of the sweat shop. The gypsy element has vanished completely, but the sense of oppressed (makers) and oppressors (money) has not. The Flamenco singer (Adrian Clarke) becomes a tuxedoed, microphone-wielding host-show zombie, stalking the joint throughout, clearly identified with the dark themes of duende and death. This too seems right. The concentration of the whole staging is horribly compelling.

A side benefit of the glazed, eyes-front demeanour of principals and chorus is that it gives the musical team a chance to shine, an opportunity well grasped. The wild sweep of de Falla's choral and orchestral writing is well caught by conductor Martin André and the Opera North Orchestra. The chorus itself is on the small side to get across the full visceral impact of the wordless cries in the Intermedio, but sings with stylish precision. The principals are uniformly strong; the young Italian-American tenor Leonardo Capalbo makes a winning and credible lather-jacketed antihero, and Mary Plazas' slim, vulnerable Salud is most affectingly sung and acted. For her, this production is a personal triumph. If Richard Coxon's transvestite "worker" pulls focus at times, that's no fault of his - this, I feel, is the only notable miscalculation in Alden's otherwise gripping and breathtaking production.

Why is it sung in Spanish? With the exception of Plazas none of the principals seems remotely at home with the Andalusian dialect. Some of it doesn't sound like any language known to man. I suppose, like singing Oedipus Rex in Latin, all this has the effect of monumentalising the tragic action - though a little devil on my shoulder prompts me to say the main benefit's that the audience will be much less likely to cotton on to the fact that what the principals do has scant reference to what they say. When Zemlinsky's glorious short opera The Dwarf, which preceded the de Falla, worked so well in English, why not trust the vernacular here too?

De Falla's reliance on offstage atmospherics a la Cavalleria Rusticana and the stasis of what action there is reveal his theatrical inexperience, and make La vida breve a very hard act to pull off in the theatre. By embracing its longeurs rather than disguising them, Alden's radical revision makes for a memorably focussed theatrical event without throwing out the musical baby with the bathwater. This, I submit to the diehards, is what contemporary opera production ought be about.

© Christopher Webber 2004 in Zarzuela.net

|