|

German and English contemporary composers German and English contemporary composers

Uroboros Ensemble/Gwyn Pritchard - conductor

Peter Helmut Lang - Dominoeffekt (World premiére)

Joe Cutler - 3 Quiet Pieces

Lothar Voigtländer - Salmo Salomonis (UK premiére)

James Weeks - The Catford Harmony (World premiére)

Ross Lorraine - end piece (World premiére)

Johannes Hildebrandt - Bruchstück II (UK premiére)

Gwyn Pritchard - Ensemble Music for Six

Karl Heinz Wahren - A Capricious and Romantic Meeting (World premiére)

Rowland Sutherland - flute

Christopher Redgate - oboe

Peter Furniss - clarinet

Fiona McNaught - violin

Bridget Carey - viola

Clare O’Connell - cello

David Leiher Jones - piano

Paul Archibold - electronics

The Warehouse, London April 10th 2008

Standing room only at the Warehouse last night, where an audience comprising just about every concert-going demographic you can imagine (children, students, professionals) enthusiastically received a concert of new music by German and English composers given by the outstanding Uroboros Ensemble.

For some of us, the evening had begun with the pre-concert discussion with the composers, led by the broadcaster and writer Ivan Hewett. This was not quite so well attended, but proved interesting to those who had bothered to make the effort. (It was a bit annoying that the talk finished so early, giving us a 45 minute break in which to do not much, but I can understand Gwyn Pritchard wanting a decent rest before the concert began.)

The discussion illuminated the background to this concert. Gwyn Pritchard explained that Uroboros see part of their mission as introducing to the British public music from abroad that is not commonly heard here, this concert focusing on some of the best German composers that are not often performed in the UK. Johannes Hildebrandt, one of the featured composers, has a festival in Weimar that Uroboros will be performing in later this year - a sort of return leg. In fact, Hildebrandt chose most of the German music presented at last night’s concert.

There were some entertaining moments as Hewett offered his opinions as to the influences/aspirations that he could detect behind Hildebrandt’s and Peter Helmut Lang’s music, only for the composers to politely disagree. For the record, I agree with Hewett that the introduction to Hildebrandt’s Bruhstück II instantly recalls Brahms. Hildebrandt and Lang* were perhaps being coy, or maybe Hewett and myself listen in a different way to them. Other observations from the pre-concert talk I shall work into the review below.

The concert began with Lang’s Dominoeffekt, scored for flute, clarinet, violin, cello and piano. To quote from the programme notes: “a piece inspired by the 30 minute movie Der Lauf der Dinge (The Way Things Go) by the Swiss filmmaking duo Peter Fischli and David Weiss. The film documents an impressively long causal chain of everyday events. There are some moments in the music where you may think you hear a standing domino slowly moving out of balance and then fall, evoking a chain reaction that starts the ball rolling. In fact everything in the composition seems to be connected to everything else. Nevertheless you shouldn’t read Peter Helmut Lang’s music as just illustrating physical objects and events. There is also a poetic quality to it that allows the listeners to make up their own images and explanations.”

I like the last sentence very much. I did indeed find the music poetic, and thought of many images to go with it. It features an alert rhythmic pulse, almost a kind of dance music, that instantly captivates the listener. This alert mood is then contrasted at times with a ‘freeze-frame’-type effect, the music appearing to move in slow-motion. The domino-effect is clearly recognizable, as events fall-in on themselves. I was most impressed with Rowland Sutherland’s playing in this piece - we heard the full range of flute colours, and were spoilt by his sensitive and dreamy pianissimo playing. He was superb throughout the concert.

Next on the menu was Joe Cutler’s 3 Quiet Pieces, scored for flute, violin, cello and piano. These had been written over the Christmas of 2003/2004 as therapy, following a very loud piece that he had just composed for a large amplified ensemble; in fact, the title had come before the piece. Cutler suggested in the pre-concert discussion that in some ways the composition failed, as the second piece wasn’t very quiet, only for Pritchard to interject and point out that it was very delicate and in-keeping with the pathos of the work. The first piece opened with a cryptic short-long rhythm** on the cello, followed by ensemble block-chords and ripples on the piano. It was certainly a quiet piece. The second was energetic, with exciting repeated-notes high on the piano, and later a violin and piano unison passage that strongly suggested Messiaen. Once again Uroboros showed a great flair for balancing dynamic and timbre. The third piece was a study in phase effect, recalling Reich et al. Its calming hypnotism reminded me of similar pieces by Basil Athanasiadis. Cutler’s own description of ‘devices wobbling’ was apt. All in all, a composition I’d love to hear again.

Lothar Voigtländer’s Salmo Salomonis followed - a piece for oboe and electronics. Here, the programme note was integral to the appreciation of the piece: “From the Wisdom of Solomon the following saying has come to us ‘Wherever there is chatter there will also be anger. He who keeps his lips sealed at a time of anger is wise.’ The present chamber piece is completely free to interpret, and for this concert will be complemented by electro-acoustic material which allows the funny-sarcastic, but at the same time pensive, interpretation of the Solomon quotation to appear in a new way.”

The piece suffered a false-start due to temperamental amplification, but proved very interesting once underway on the second attempt. The oboe’s part is captured, treated, and relayed through speakers as in many other pieces, but always the quotation from Solomon looms large in the mind of the listener. The oboe as protagonist, choosing whether to keep his lips sealed when confronted with the anger of the electronics? This is where my thoughts were led. In the second-half of the piece, the performer begins to utter syllables (in German, presumably the Solomon quotation, although this wasn’t specified) which are also picked-up and treated electronically. The quiet echoes had a profound effect, coming across like deranged inner voices. I have no idea how loudly Christopher Redgate was meant to speak the fragmented text, but I couldn’t hear it clearly enough to identify anything other than the language; it had the effect of watching an eccentric talking to himself. The piece reaches a fantastic, psychedelic climax, before moving towards a mellower mood. I was left with a feeling that electronic permutations of oboe sound had been thoroughly explored. The very last sound is an unexpected gong from the electronics.

The final piece of the first half was James Weeks’ The Catford Harmony, scored for violin, cello, flute, oboe, clarinet, and piano - impressively performed without conductor. The title refers to the great eighteenth-century American collections of hymns and sacred songs, named after the places in which they were sung. Weeks has recently moved to Catford, hence the name. (Has it been performed in Catford? Shouldn’t it be called The Waterloo Harmony?) Weeks writes that the piece: “...continues my abiding interest in elemental or rudimentary musical materials: made out of lines which are very restricted in pitch and rhythm (sometimes using just a few pitches and one or two different lengths of note).”

Hewett commented in the pre-concert discussion on the lack of dynamics, in fact it starts forte and continues without change. At times the texture was vibrant and interesting, at other times, particularly when only one or two instruments were playing, it sounded more like my max-msp note-randomizer patch. These sparse moments were infrequent, most of the piece featuring quite dense instrumentation which to my ears sounded expressionistic; bold, primary colours.

The second half began with end piece by Ross Lorraine, for violin, viola, cello, clarinet, oboe, flute and piano. From the programme notes, Lorraine did not want to provide information about the piece, seeking a ‘naive’ response from the audience, and I wonder how differently I would have listened to it had I not attended the pre-concert discussion. Lorraine explained that the title referred firstly to the end of a compositional phase that he had just arrived at, and secondly to the fact that the structural climax of the piece comes very near the end. It was composed with sequencers - Lorraine working with pure sound - and finally notated once complete.*** The composer explained that he has always had a love/hate relationship with notation, and envied visual mediums where artists can work without such obstructions.

end piece is very detailed in its construction, and I felt that I would benefit greatly from a second hearing in order to communicate a more lucid and detailed response. The sequencing is clear - for instance passages with the strings and wind playing clusters, with sudden interruptions high on the piano, are reversed later on with low rumbles on the piano and bursts high in the flute register. The various motifs are combined to great effect at the climax late on, after which the piece unexpectedly ends tonally (an A7 chord?), finally drifting out on a solo viola note.

After this came Johannes Hildebrandt's Bruchstück II for string trio (‘bruchstück’ meaning fragment). Hildebrandt explained that the piece was not in his typical style, and that it constituted a friction between two worlds. These two worlds are savagely contrasting - the first in a tonal, yet stark language, the second aggressive, chaotic and dissonant, with the first returning at the end.

The penultimate piece was Gwyn Pritchard’s Ensemble Music for Six (violin, viola, cello, clarinet, flute and piano), a transcription finished in 2003 of piano pieces he had written before 1976. Pritchard explained earlier that the transcription process had led to material being added, and at times I struggled to imagine how this music could be performed on solo piano. The music has certainly outgrown its genesis, and appears wonderfully idiomatic for its present forces. There were four pieces in all, the second and fourth being very short, barely a minute each.

The last piece of the concert was Karl Heinz Wahren’s A Capricious and Romantic Meeting. I liked the programme notes very much:“A Capricious and Romantic Meeting for three woodwind instruments, piano and three strings is a dialogue between all seven instruments in three movements. I do not compose pictures, I do not expect the listener to understand my ideas exactly or feel at one with them. I cannot object if the associations the music has for the listener are quite different from the ones I had in mind. The main thing is that the music appeals to them at all. Artistic creation is an attempt to distance oneself from the reality of life, to subjectively alienate it with the chosen material and thus communicate to an interested public images of the way one feels about reality with taste and vitality; but finally this is all a matter of opinion.”

Bravo. I wish more composers would write such honest and refreshing comments. Unfortunately, I did not warm to the music at all. It began with muted strings in close harmony, a Korngoldian, wistful, Romantic pastiche with occasional cheeky rhythms. I kept waiting for the twist... would it be ironic?... would it be deconstructed?... would it be surprising?... funny?... strangely out of place?... or maybe just a straightforward neo-romantic composition? In the final analysis, it seemed to be none of these. I don’t know what Wahren was trying to achieve, and from his programme notes I surmise that I don’t need to know his intentions, but find an interpretation myself. All I can say is that I didn’t like it. If it was a romantic meeting, it seemed alchohol-fuelled and a bit sleazy to me. The second movement, with it’s Kodaly-like opening on the solo cello, and the third movement, which reminded me of Rozsa, did nothing to change my mind. (I like Korngold, Rozsa and Kodaly very much, I hasten to add.) The audience greeted it warmly, but I was baffled, as was another composer sitting near to me. It seemed out of place with the other pieces.

Aleks Szram

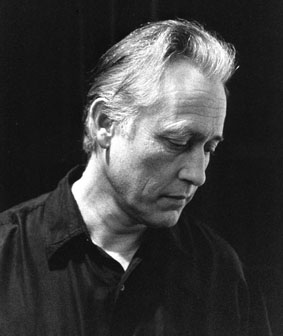

*Lang constitutes serious competition for Daryl Runswick in the ‘coolest beard in contemporary music’ stakes.

** “That would be an iambic rhythm” cry the musos.

***Lorraine likened this to Beckett’s technique of writing in French before translating into English, finding a benefit from the distance that this gave him.

|